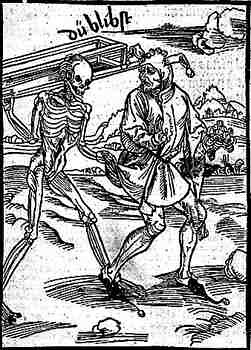

I love this time of year. Time for scary stuff, like more mad cow disease news, and brand-new Supreme Court deliberations, and creepy pictures, like this one of a virus penetrating a human cell. That's right, folks, it’s Pandemic Flu Awareness Week, and that means learning all about how the influenza virus works, what it can do to you when it gets its hemagglutininous hands on your sialic acid receptors, and lastly, getting worried enough to pay attention to what the powers that be are doing (or not doing) about it all.

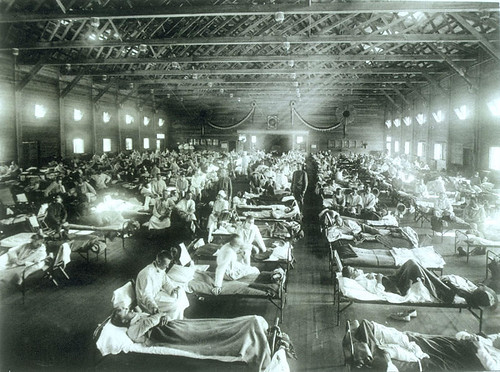

I love this time of year. Time for scary stuff, like more mad cow disease news, and brand-new Supreme Court deliberations, and creepy pictures, like this one of a virus penetrating a human cell. That's right, folks, it’s Pandemic Flu Awareness Week, and that means learning all about how the influenza virus works, what it can do to you when it gets its hemagglutininous hands on your sialic acid receptors, and lastly, getting worried enough to pay attention to what the powers that be are doing (or not doing) about it all.The synchronicity of this is also fairly creepy. Over the last couple years I've been learning about the great flu pandemic of the early 20th century. Just a few years ago PBS ran a documentary about it, Influenza 1918. Then last week, baited by the Borders' 3 for 2 sale, I picked up a copy of John M. Barry's fine book, The Great Influenza, an account of the 1918 pandemic of the influenza virus known affectionately among scientists as good old "H1N1". And I've been buttonholing friends and innocent bystanders with all the gory details ever since.

In that exponential way the quest for knowledge expands when a curious reader is exposed to the virus of a fascinating concept, I started reading everything I could find to try to understand what all this was about. I knew something about viruses from the first literary Big Scare, brought on by Richard Preston's The Hot Zone, which gruesomely detailed the habits and effects of the Ebola and Marburg viruses. What I didn't know was that the 1918 pandemic killed "more people than any other outbreak of disease in human history," as Barry put it in his book. And it did it in only 2 years' time. The last two days the papers have been full of the latest Bush talking points about how to prepare for a pandemic. Yesterday, as I was working on this post, I heard NPR announcing that a couple teams of scientists have made a major breakthrough, identifying the 1918 H1N1 killer as a bird flu virus that had jumped species directly into humans. The story has been on the online NYTimes for two days now.

Influenza virus is believed to have originated in wild birds. The one that particularly worries scientists today is known by the catchy name “H5N1”. You've probably heard plenty about this by now: the intermittent reports of avian flu in Southeast Asia, the slaughter of over a million domestic fowl in Hong Kong, the deaths of a Thai woman and her daughter that pointed to a possible first human-to-human transmission, the surprise deaths in a wealthy Jakarta suburb of a father and his two young daughters who had no known contact with birds.

Influenza virus is believed to have originated in wild birds. The one that particularly worries scientists today is known by the catchy name “H5N1”. You've probably heard plenty about this by now: the intermittent reports of avian flu in Southeast Asia, the slaughter of over a million domestic fowl in Hong Kong, the deaths of a Thai woman and her daughter that pointed to a possible first human-to-human transmission, the surprise deaths in a wealthy Jakarta suburb of a father and his two young daughters who had no known contact with birds.Why is this so worrisome? While the virus has demonstrated that it can transmit itself bird-to-human, it has not been positively identified as being able to transmit human-to-human (though some circumstantial evidence exists that it may have). And in human-to-human transmission lies the potential for a pandemic. If it establishes itself as a human vector, it can devastate untold numbers of people around the world because, since no such virus has ever attacked the current living human populace, no one now living has developed any immunity to it.

Transmission is a tricky business, because viruses have an almost sci-fi ability to mutate. Most of them are species specific; they may only infect horses and birds, or birds and pigs, or humans and monkeys. Some can adapt to leap the species barrier from, say, bird to human, but once into the new species, cannot go any further. Others, though, can adapt to not only leap that barrier, but settle in and spread throughout the new species, and these adaptations are made possible by genetic mutation. But more on that in a minute.

Transmission is a tricky business, because viruses have an almost sci-fi ability to mutate. Most of them are species specific; they may only infect horses and birds, or birds and pigs, or humans and monkeys. Some can adapt to leap the species barrier from, say, bird to human, but once into the new species, cannot go any further. Others, though, can adapt to not only leap that barrier, but settle in and spread throughout the new species, and these adaptations are made possible by genetic mutation. But more on that in a minute.Yesterday Bloomberg reported:

“A 23-year-old Indonesian man who died last week tested positive for bird flu, increasing to seven the number of human fatalities from the disease, a doctor at the Sulianto Saroso hospital in Jakarta said.No confirmation. But the more recent deaths in Jakarta also occurred where no direct contact with fowl was known to have taken place. Let’s take a few steps back, and see what we’re dealing with.The World Health Organization laboratory in Hong Kong will need to confirm the local test results. The UN agency has so far confirmed four human fatalities from H5N1, a deadly strain of the avian influenza virus, in Indonesia....

More than 140 million chickens have been slaughtered in Asia because of concern the H5N1 strain of the virus may mutate into a form easily transmissible between humans. As humans are unlikely be immune to such a virus, the World Health Organization is concerned it may trigger an influenza pandemic like the one that led to more than 40 million deaths worldwide in 1918.

The highly pathogenic H5N1 is endemic in poultry in many parts of Indonesia, WHO said in the statement, citing the Food and Agriculture Organization. More than 10 million chickens have been killed by the virus since the outbreak in 2003, Agriculture Minister Anton Apriantono said on Sept. 19.

There has been no confirmation of human-to-human transmission of the virus. One case of probable human-to-human infection occurred in Thailand last year, when a mother and her daughter died from the disease.”

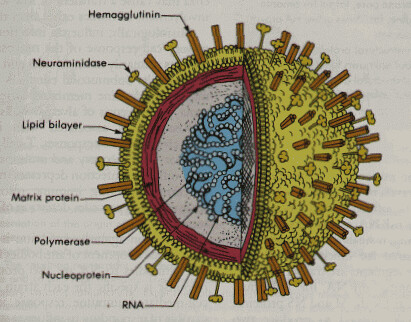

The influenza virus, like all viruses, has only one known function: to replicate itself. It does this by invading a host cell, hijacking the gene-making machinery inside, and forcing the cell to reproduce so many of the original virus that the sheer number of them finally bursts open the cell and kills it. The newly-escaped brood of up to a million new viruses then sets out to do the same to the nearest suitable cells.

The influenza virus, like all viruses, has only one known function: to replicate itself. It does this by invading a host cell, hijacking the gene-making machinery inside, and forcing the cell to reproduce so many of the original virus that the sheer number of them finally bursts open the cell and kills it. The newly-escaped brood of up to a million new viruses then sets out to do the same to the nearest suitable cells.What makes a suitable cell? When a bird gets the flu, it goes for the gastrointestinal tract. In human beings, it attacks the respiratory system, which means the epithelial cells that protect the surface of the lungs and bronchi. (While it may take the virus less than 72 hours to denude the respiratory surfaces of epithelial cells, it will take the body weeks to build them back up again--if it survives). In the meantime, their destruction can allow the virus to penetrate deep into the lobes of the lungs, resulting in viral pneumonia, or let bacteria in, causing bacterial pneumonia. In either case, the resulting war between the invader and the body's immune system can wreak such destruction that, in the worst cases, the capillaries can be destroyed by killer proteins and the lungs fill up with fluid, blood, dead cells, collagen, and fibrin, drowning the victim or causing heart failure or death by exhaustion from the sheer strain of trying to breathe.

Normally when a micro-organism invades the body, the immune system rallies to attack it, and it recognizes the foreign invader by the antigens it carries. Once it has engaged the enemy in combat, the immune system "remembers" what that enemy looks like because the antigens have caused it to release antibodies specific to those antigens. Thereafter, any further attack will rally the same antibodies, resulting in a response so swift and effective that the body can be said to have developed an immunity to the invasive organism. The principle of vaccination capitalizes on this process by introducing antigens into the body in a controlled way so the immune system can learn to recognize them and create the antibodies that will immunize the body in case of future encounters.

The antigens of the influenza virus consist of two types of protrusions carried like spikes all over its surface: hemagglutinin (the "H" factor), which enables it to bind to the host cell, and once inside, break into the genetic machinery, and neuraminidase (the "N" factor), which destroys the sialic acid of the host cell and allows the newly-created viruses to escape the dying cell and explode into the body. The flu virus' RNA-based genetic code provides no safeguard against mutation as it replicates in the hijacked cell (resulting in the creation of literally millions of different kinds of "quasi-species" in the course of a few hours), and unlike many other viruses, it can survive the mutation of its antigens and continue to function. Worse, it has the demonic ability to mutate not only properties of these antigens when replicating (antigen drift), but even entirely new antigens if it comes into contact with other different types of flu viruses (antigen shift). "Antigen drift" hides a virus from an immune system that once recognized it, resulting in epidemics, which is why flu vaccines have to be constantly changed and updated. But “antigen shift”, essentially the creation of a brand-new type of virus that the immune system has never encountered in any form, is what causes pandemics, the ultimate concern scientists have about the H5N1 virus. This means if a human being contracts the H5N1 virus from a bird, and also happens to be carrying a human flu virus, the two organisms may collide during replication, where the loose strings of RNA genes may come apart and reassort with each other, suddenly resulting in a virus that inherits the human virus’ ability to transmit from person to person. The same can happen when a 3rd party “mediates” the mutation, as with pigs, which are susceptible to both avian and human viruses. If a pig happens to carry both at the same time, it may pass to its handlers a mutant that may go on to infect other humans.

The antigens of the influenza virus consist of two types of protrusions carried like spikes all over its surface: hemagglutinin (the "H" factor), which enables it to bind to the host cell, and once inside, break into the genetic machinery, and neuraminidase (the "N" factor), which destroys the sialic acid of the host cell and allows the newly-created viruses to escape the dying cell and explode into the body. The flu virus' RNA-based genetic code provides no safeguard against mutation as it replicates in the hijacked cell (resulting in the creation of literally millions of different kinds of "quasi-species" in the course of a few hours), and unlike many other viruses, it can survive the mutation of its antigens and continue to function. Worse, it has the demonic ability to mutate not only properties of these antigens when replicating (antigen drift), but even entirely new antigens if it comes into contact with other different types of flu viruses (antigen shift). "Antigen drift" hides a virus from an immune system that once recognized it, resulting in epidemics, which is why flu vaccines have to be constantly changed and updated. But “antigen shift”, essentially the creation of a brand-new type of virus that the immune system has never encountered in any form, is what causes pandemics, the ultimate concern scientists have about the H5N1 virus. This means if a human being contracts the H5N1 virus from a bird, and also happens to be carrying a human flu virus, the two organisms may collide during replication, where the loose strings of RNA genes may come apart and reassort with each other, suddenly resulting in a virus that inherits the human virus’ ability to transmit from person to person. The same can happen when a 3rd party “mediates” the mutation, as with pigs, which are susceptible to both avian and human viruses. If a pig happens to carry both at the same time, it may pass to its handlers a mutant that may go on to infect other humans. At this point there is uncertainty as to whether H5N1 has yet mutated in this way, though if it had, its virulence would have likely begun killing far more people by now. The World Health Organization reports that as of 9/29/05, there were 116 cases resulting in 60 deaths--a mortality rate of 52%. But even if the transmission issue is still uncertain, there is absolutely no doubt among scientists everywhere, from those at WHO to the Center for Disease Control, that it is a very real danger. The announcement yesterday by the teams of researchers at the CDC confirms that the pandemic flu of 1918 developed just as they fear H5N1 is developing.

At this point there is uncertainty as to whether H5N1 has yet mutated in this way, though if it had, its virulence would have likely begun killing far more people by now. The World Health Organization reports that as of 9/29/05, there were 116 cases resulting in 60 deaths--a mortality rate of 52%. But even if the transmission issue is still uncertain, there is absolutely no doubt among scientists everywhere, from those at WHO to the Center for Disease Control, that it is a very real danger. The announcement yesterday by the teams of researchers at the CDC confirms that the pandemic flu of 1918 developed just as they fear H5N1 is developing.Here is the paradox: the more virulent the influenza virus, the more violently the immune system reacts, and the healthier the immune system is, the stronger that reaction will be. This is why the pandemic of 1918 killed so many young adults. The deaths of young, healthy people in Asia who contracted H5N1 is a warning signal.

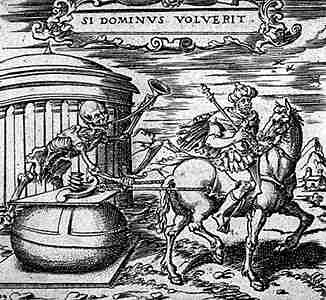

What can we do? It's not as if we can get into the lab and whip up our own genetically recombined virus for a vaccine. Mike Davis, author of Monster at Our Door, outlined in Common Dreams last year the many problems that would prevent an appropriate and sufficient response to a pandemic: lack of a vaccine and limited production capacity, lack of a vast-enough vaccine delivery system, and lack of public knowledge or interest. Add to that John Barry's more recent assessment: drug-resistant bacteria, insufficient medical facilities, long waiting lists and insufficient manufacturing capacity for antiviral drugs like Tamiflu, massive economic and social disruption, and of course, the deaths, for which current casket inventories would be completely inadequate, resulting in the piling up of corpses in homes and everywhere else.

What can we do? It's not as if we can get into the lab and whip up our own genetically recombined virus for a vaccine. Mike Davis, author of Monster at Our Door, outlined in Common Dreams last year the many problems that would prevent an appropriate and sufficient response to a pandemic: lack of a vaccine and limited production capacity, lack of a vast-enough vaccine delivery system, and lack of public knowledge or interest. Add to that John Barry's more recent assessment: drug-resistant bacteria, insufficient medical facilities, long waiting lists and insufficient manufacturing capacity for antiviral drugs like Tamiflu, massive economic and social disruption, and of course, the deaths, for which current casket inventories would be completely inadequate, resulting in the piling up of corpses in homes and everywhere else. How many corpses would H5N1 leave in it's wake? Barry's equation is that a new flu virus will make between 14-40% of the population symptomatic. Using that percentage, and using the mortality rate of 52% mentioned above, here in the United States we could expect from 44 million to 115 million to fall ill, and from 23 million to 58 million dead. We have never, ever experienced that kind of devastation: 20% of our populace dead, and the majority of them, if true to the 1918 virus, young adults.

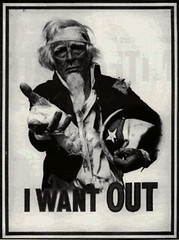

So now the government has been all over the news the last couple days crowing about all the work they're going to do on this issue.

You saw the Katrina response.

What will you be expecting?

No comments:

Post a Comment